Student homeless numbers climb over decade

November 2, 2020

A new report from the UCLA Center for the Transformation of Schools chronicles the realities and challenges of student homelessness

, which currently affects 269,000 K-12 students in California. “State of Crisis: Dismantling Student Homelessness in California” also makes specific recommendations on how to solve the crisis through collective action at the local, state and federal level.

“Schools, for far too long, have been asked to solve this problem all alone. It’s unfair and it’s unreasonable,” said Tyrone Howard, faculty director of the Center for the Transformation of Schools, during a webinar discussing the report’s release on Oct. 20.

According to the report, California student homelessness has grown by 48 percent in the last decade, however authors Joseph P. Bishop, Lorena Camargo Gonzalez, and Edwin Rivera note that they expect homelessness to increase due to unemployment stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic.

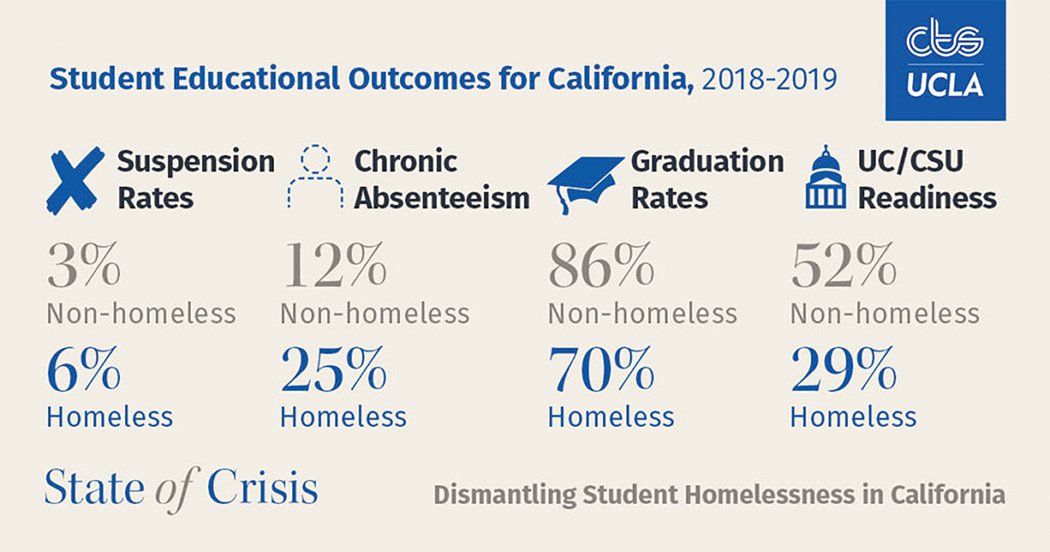

The crisis affects the educational outcomes of students experiencing homelessness. For instance, 70 percent of homeless students reach graduation, compared to 86 percent of non-homeless students. The report also identified students who are disproportionately affected by homelessness — Latinx students make up 70 percent of the homeless student population (54 percent of all students) and Black students make up 9 percent of the homeless student population (5 percent of all students). Students who identify as LGBTQ also face higher rates of homelessness.

While the need to address the issue is clear, the report notes several difficulties in quantifying student homelessness. Identifying students is problematic due to their highly mobile nature, but also due to family shame and stigma around revealing their living situation. Families many not see themselves in crisis, even when they are “doubled up” and living with multiple other families.

Erin Simon, assistant superintendent of school support services for Long Beach Unified School District, said all district staff, including enrollment clerks, school nurses and teachers, receive intensive ongoing training on identifying the signs of homelessness, such as a parent’s inability to provide proof of residency during enrollment.

“I believe that teachers are one of the most vital staff to receive training, and why? Because teachers spend the majority of the school day with students, and if they are trained properly, they will be able to identify signs of homelessness quickly, efficiently and confidentially, in order to lessen students’ feelings of isolation,” she said.

Varying definitions of homelessness across different federal programs also complicate the issue. For instance, families living “doubled up” in a motel would qualify for supports under the McKinney Vento Act, however they would be considered “housed” under HUD criteria.

The report authors conducted focus groups and interviews with more than 150 stakeholders, and included glimpses into the lives of students experiencing homelessness and the educators charged with supporting them.

Based on this research, the authors found that support systems currently lack capacity — both in terms of people power and funding — to serve these students.

Pamela Hancock, director of foster and homeless education with the Office of Fresno County Superintendent of Schools, said many of her liaisons are also working with foster students and in other roles, and federal funding to support homeless students ($52/student) is far lower than the support given to foster kids ($450/student).

“There is really the lack of time to fulfill our responsibilities and there’s also the lack of funding,” she said. “Understand that we never get state funding, we’re only getting funded through the federal funding stream.”

Students experiencing homelessness are often overlooked or misunderstood, leading to negative educational outcomes (see graphic above). Two teachers in Anaheim shared that an English class assignment where students wrote about a memory opened their eyes to the trauma many of their students have faced, including poverty, neglect, abuse and homelessness.

“Our job is to teach English, but how do you get a student to care about Shakespeare or argumentative essays when their basic human needs are not met?” said teacher Jennifer Ortiz.

Ortiz and fellow teacher Jessica MacCaskey realized they needed to broaden their scope of practice and become trauma-informed educators to serve these students’ needs, and it has greatly improved their classroom culture.

The report authors recommend a number of changes at the federal, state, city/county and school district level to address the issue, including:- Establish a standard definition of homelessness.

- Adequately fund the McKinney Vento Act to drive more federal dollars to state and local systems.

- Target more of Local Control Funding Formula dollars to helping students experiencing homelessness.

- More longitudinal “cradle to career” data tracking to identify students.

- More coordination between school districts, city and county agencies to provide access to resources.

- More city-led efforts that focus on K-12 and college-level rapid rehousing.

- Expanding afterschool programs.

- Align district resources for students experiencing homelessness with LCAP goals.

- Encourage more districtwide strategies for serving students experiencing homelessness.

Read the full report at

http://transformschools.ucla.edu/stateofcrisis/

.Report from UCLA urges collective action to solve California student homelessness