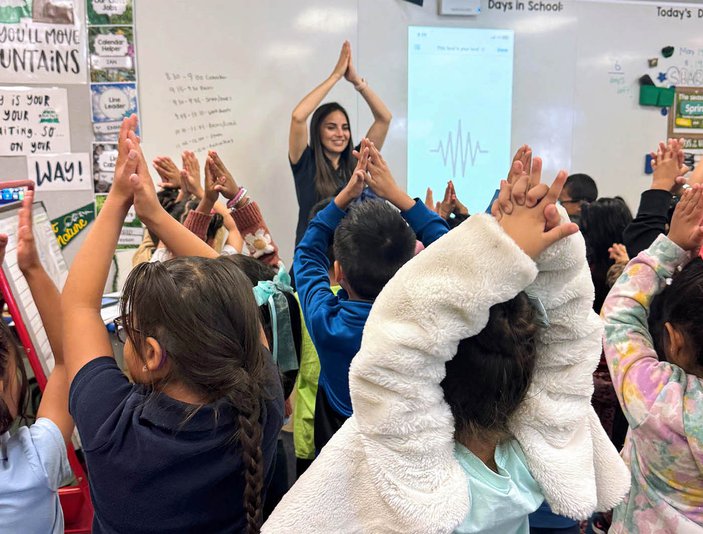

Cristina Brown leads an interactive lesson on phonemic awareness during her TK reverse mainstream time.

The following story was written by Kate Strauss, communications and media consultant for Buena Park School District.

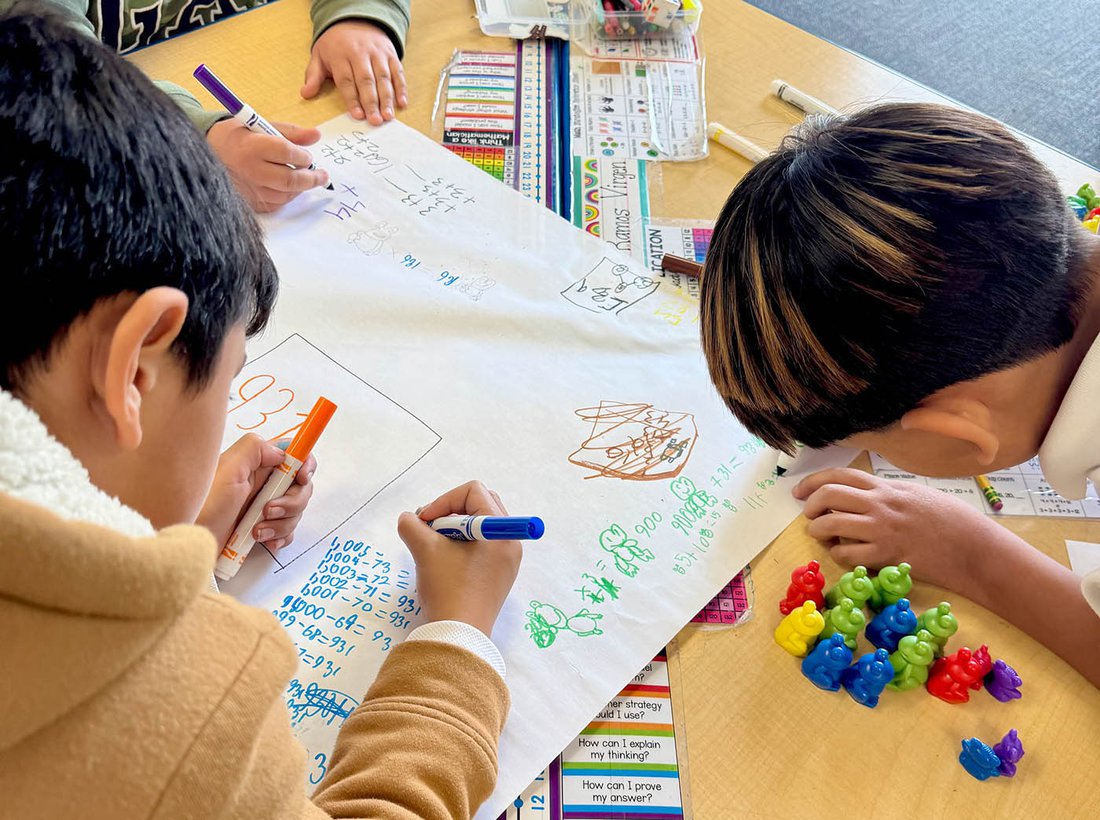

Suzanne Huerta writes the number “931” on the whiteboard in room 36 and gives the students this direction: “If 931 is the answer, what is the question?” Matthew and Angel both reach for a blank piece of paper and begin developing an original math problem that will yield the answer 931. Matthew draws a series of number groupings and creates a subtraction question: 1,004 - 73 = 931. Angel takes a different approach using gridmarks that represent frogs: If you combine 900 frogs with 31 frogs, how many frogs will you have? At Huerta’s direction, Matthew and Angel turn and talk to each other, sharing these divergent strategies and articulating the thinking behind them, and then they join a classwide conversation about the myriad mathematical questions whose answers are all 931.

The discussion engages every student, and the exchange of ideas reveals numeric layers and connections on a complex level. Not surprisingly, the lesson follows the general education pacing guide for grade-level content standards. But in this class, each pair of math students is comprised of one general education and one special education student. And this reverse mainstream model has yielded benefits that extend well beyond academics.

Reverse mainstreaming is fairly new at Whitaker Elementary School in the Buena Park School District. Instead of bringing special education students to the general education class, the general education students go to the special education class, which keeps the special education teacher as the lead and the surroundings familiar to the special education students. Reverse mainstreaming requires that general education students comprise more than 50 percent of the students in a classroom. In this case, Huerta’s math class includes her 13 special education fifth-graders plus 14 general education fifth-graders from a colleague’s combination class.

Huerta is a familiar name in the elementary math world. She was named California’s 2024 finalist for the Presidential Awards for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching and a Top 10 Educator in Orange County for her work using cognitively guided instruction to teach mathematics to students with disabilities. She has seen how impactful CGI methods have been in her class. Indeed, research shows that students’ ability to explain their own thinking and discover mathematical principles through conversation greatly enhances their understanding. But this reverse mainstreaming model has added another layer.

The general education students, representing an arbitrary assortment of math ability levels, started coming to Huerta’s special education classroom for 1.5 hours of math each day.

“It was amazing,” says Huerta, “because the gen ed kids seemed to feel comfortable sharing their thinking from the start and showing initiative, and my students were able to pick up on their ideas and piggyback on them.”

The biggest surprise to Huerta was how much the general education students loved coming and how attentive they were in the lessons and with each other. “They grew to be very protective of the special education students,” says Huerta. “They were all so compassionate and understanding.”

At Open House in April, parent after parent of the general education students told Huerta how beneficial this class has been for their children, both academically and socially. One parent shared that she had noticed a change with her child being more patient and kind with peers and younger siblings.

“I wish all classrooms could have this experience,” says Huerta.

A student named Jaxon in Huerta’s class bonded with one of the general education students named Marcel. Jaxon’s autism generally keeps him as an independent learner who doesn’t socialize with others, but Marcel’s patience somehow found an entry point. When Marcel returned to class after a few days of being sick, Jaxon gave him a hug. During summer school, Marcel called Jaxon over to sit and eat breakfast with him and his friends.

“It’s not just about building better students, but building better people,” says Whitaker Principal Stephanie Williamson. “When you come here, you will find a happy community where children know they belong. They know their self-worth, and they’re learning how to use their voices. That’s where we’re starting. And we’re starting young.”

At Whitaker, “young” includes Cristina Brown’s special education transitional kindergarten class, where general education teachers have been bringing their students into Brown’s classroom for shared reading time. At first, this reverse mainstream time was limited to morning songs, but it soon grew to include lessons on phonemic awareness and the simple manipulation of sounds. From there, the teachers added shared mathematics time, with choral counting and a daily “notice and wonder” math activity. And all the while, empathy and friendships among the students blossomed.

Special education students with more limited verbal skills now had more social models, and general education students who tended to be quieter started speaking more because they had more available partners. They also learned to be empathetic, helpful, and open to differences. “When you start this young,” says Brown, “the stigmas and ideas about difference never have the chance to develop because students have grown up and shared learning and play time together. It’s good for everybody.”

Today, Brown shows a photo of blueberries in varying pile sizes on the smartboard to the students sitting criss-cross-apple-sauce on the carpet.

“How many blueberries do you see?” she asks. “Talk to your partner.”

The students turn and talk to their partners, and then they share their ideas with the class. Nicolas thinks each pile has five blueberries in it. “Does everyone agree with Nicolas, or does anyone see something different?” asks Brown.

She points to the first pile of blueberries, which has only one blueberry in it. “How many are here?” she asks. “One!” says the class. “OK, everybody write a ‘one’ in the sky!” Thirty-five hands shoot into the air and draw a “one.” The students continue with the next blueberry group, and they soon discover that the number of blueberries increases for each group by one blueberry: “Two!” “Three!” “Four!”

“If this is a pattern,” says Brown, “how many blueberries should be in this next group here?” “Five!” The students draw a five in the air, and then one student adds, “High five!” and high-fives her partner.

That moment of collaboration and congratulation captures the essence of this reverse mainstreaming model.

“The students have an incredible opportunity to learn from one another in meaningful ways,” says Superintendent Dr. Julienne Lee. “They’re building strong peer relationships and developing empathy, self-confidence, and social skills together.”

General education and special education partners in Suzanne Huerta’s class develop an original math problem that will yield the answer 931.